This week, my head has felt like a washing machine stuffed full of clothes, cycling endlessly through wash, rinse and spin. I grant you this is not the most elegant of metaphors but that’s how it’s been. I even wrote it in my notebook - Today my head is like the inside of a washing machine. Why is this I ask myself? Putting aside the various household upheavals associated with having a new boiler installed, plus getting ready for a trip to Malaga, (no complaints here - the weather looks to be sunny and mild) this feeling that my head is crowded with a jumble of different garments, tumbling about in a wash, comes I think from allowing my writing free rein.

I am not working on a single project, which is unusual for me. In the last week I’ve continued editing a short story I wrote in 2023, drafted a short chapter on a novel, and worked extensively on a poem. I am not entirely happy with any of them, though the short story has a completeness about it and a voice that I think works. The problem for me in working in three different genres at the same time, is that ideas start to crowd in, ideas emerge from the ether, for other poems, other stories, and more possibilities for the novel. Poetry is about fragmentation, but so are the novel and the short story in their genesis, perhaps this week there has been too much fragmentation; too many pieces of the jigsaw to contend with.

As a consequence, and in the hope of getting the washing out of the machine and onto the page, I’ve decided I need an ideas notebook; a notebook to capture first lines, first thoughts. Fragments. Why didn’t I think of this before?

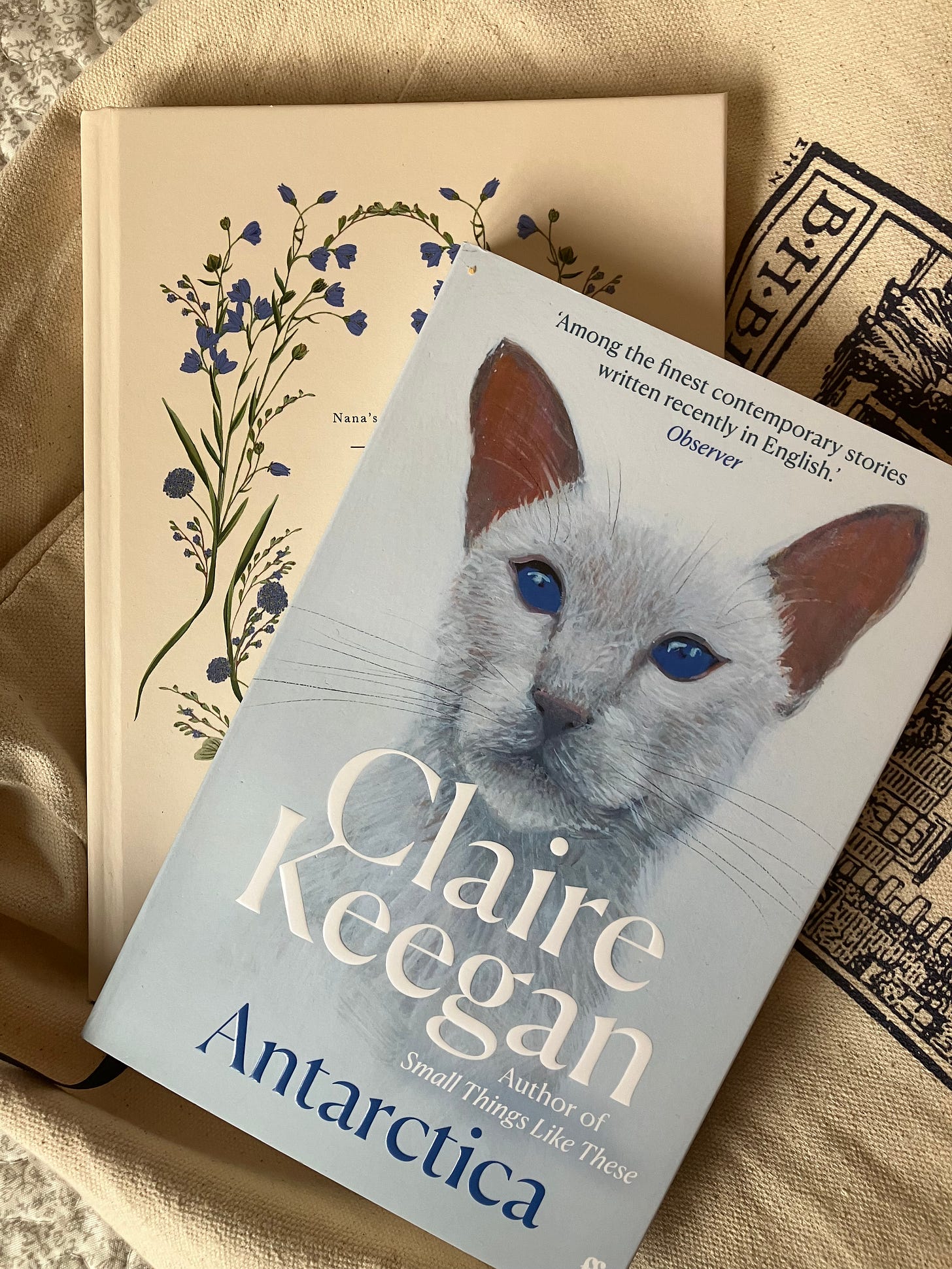

As well as the ideas generated by writing there are those that spring from reading too. This week has been no exception. I’ve been reading Antartica, by Claire Keegan - a short story collection that is every bit as good as her novellas, somewhat different in style, in that they’re more densely written, more descriptive (perhaps because they’re earlier than Foster and Small Things Like These) though the language is beyond perfect. It’s the kind of read that either inspires you or makes you want to give up altogether. It has certainly made me think about writing more short stories.

George Saunders, king of the short story and author of Lincoln in the Bardo, calls Keegan, ‘One of the greatest fiction writers in the world.’

To my mind Saunders is one of the greatest teachers of fiction in the world and on March 28th 2021 on my blog I wrote the following on just this subject -

Hi Everyone,

from tomorrow we can sit outside in our gardens with up to six people! Though if today is anything to go by, we are likely to get soaking wet and freeze to death! No need for despair however, Tuesday’s forecast is for sun, so here’s hoping that we can once again begin the slow waking from our enforced hibernation.

If we were sitting down together next week in my garden over a coffee or even a glass of wine, I would undoubtedly be telling you how I’ve just read the best book ever on writing, in particular on writing short fiction: George Saunders’ A Swim in a Pond in the Rain. Saunders has been teaching creative writing at Syracuse in the US for twenty years. ‘A few years back, after the end of one class (chalk dust hovering in the autumnal air, old-fashioned radiator clanking in the corner, marching band processing somewhere in the distance, let’s say),’ he had the realisation that ‘some of the best moments of my life, the moments during which I’ve really felt myself offering something of value to the world, have been spent teaching that Russian class.’ In this moment he decides to put down what he knows, what he’s learned; to write the book and share with us his love and deep understanding of the stories and their craft.

When you find yourself underlining every other sentence or paragraph, sending What’s App messages to your writing Buddy at all hours of the night, you know you are in the presence of genius, albeit humble. Saunders is a cool and self-effacing kind of guy. These are just, he claims, ‘thoughts according to George.’

Saunders shows us by example what we might do as writers, guiding us through the relationship with our reader and with our own words, the choices we make, the trust we place in our story – the story has a will of its own that we must listen for. And how simple it can all be – ‘You don’t need an idea to start a short story you just need a sentence.’

For Saunders the focus in his own writing has always been ‘trying to learn to write emotionally moving stories that a reader feels compelled to finish.’ Stories must be honest, create energy, every element a little ‘poem freighted with subtle meaning.’ He de-mystifies plot into ‘meaningful action,’ rejects planning, ‘A plan is nice. With a plan, we get to stop thinking. We can just execute. But a conversation doesn’t work that way and neither does a work of art. Having an intention and then executing it does not make good art.’

Editing is key; obsessive, repetitive, the application of preference, over months even years…getting to know the voice inside you, what it likes, hearing it and acting on it in the thousands of microdecisions to be made. Saunders asks, ‘How long are you willing to work on something to ensure that every bit of it gets infused with some trace of your radical preference? The choosing, the choosing, that’s all we’ve got.’

I could go on and on, but suffice to say if you want to be a better, more aware writer, if you want to be the best writer you can be, you cannot afford not to jump into the pond with George.

Now, back to 2024

Sure enough, while I was thinking of short stories and George Saunders, more inspiration arrived, in the form of this week’s Story Club, which offered an exclusive excerpt from a new book being published by Hanover Square Press on February 6, called, Why We Read: On Bookworms, Libraries, and Just One More Page Before Lights Out, by Shannon Reed.

The excerpt comes in the form of PDF Why We Read Excerpt Saunders (1). Click above on the link to this weeks’s Story Club, scroll down and you will find the PDF. It’s a fascinating account of how she set about reading Lincoln in the Bardo with her students. It has much to teach us about the process of reading and of writing. About how to trust our readers and how to trust ourselves. ‘Trust the fun,’ says George. Trust and value one’s imagination is the message.

I need to take heed

Thanks for reading

Avril x