On market day in Marseillan, on the edge of the Mediterranean, by a salt water lagoon known as the Etang du Thau, I bought a linen dress. A simple shift, in that very French shade of lavender blue, the colour of painted shutters, the colour of the horizon across the still waters of the Etang. The instant I spotted it on its market rail I knew it would be impossible to resist. I watched it for a while as I drank my coffee in the Cafe Marine. I willed someone else to come along and buy it so I wouldn’t have to do the whole, should I shouldn’t I, or, do I really need another dress, dance. Nobody did. When I finally made up my mind to buy, I imagined it would be too small. But it wasn’t. It was a generous one size fits all. It wasn’t too expensive either, these market clothes aren’t, which makes it easier to love, that, and the colour.

Later, back in the house, from the generous but unfamiliar book shelves, I picked out Rebecca Solnit’s, A Field Guide to Getting Lost. I turned to one of my favourite chapters/essays, The Blue of Distance, where Solnit ponders the problems of yearning, and the blue that is out of reach. She writes, For many years I have been moved by the blue at the far edge of what can be seen, that colour of horizons, of remote mountain ranges, of anything far away. She describes this blue as the colour of solitude and desire, the colour of where you are not. Blue, she says, according to the poet Robert Hass, is the colour of longing.

I remembered then the blue dress my mother made me when I was eight. I think I was eight, it’s hard to tell because my memories of childhood cluster around that particular age. It isn’t hard to conjure the dress. It was made from blue seersucker with pearl buttons and two rows of lace trim either side on the bodice. The fabric was patterned with tiny white bows and rippled to the touch.

It is one of the very few items of clothing I remember from my childhood. It was beyond doubt my favourite dress, the colour of a summer sky, and I felt light and altered wearing it. It had the power as clothes sometimes do, to transform. It took away the heaviness in my body, the puppy fat as the adults liked to call it, but more than that it took away the sadness in my soul. It was my mother at her best, maker of beautiful clothes.

I sometimes wish I’d kept it. I have no idea what happened to it. I wonder how it would be to see the shape and the size of it, the shape and size of the small person that was me. But then I wonder would meeting the dress mean the memories I hold of it would be lost? Could the object really live up to all it has come to represent for me, that small, blue world, that was the better part of childhood. Would I be disappointed by the reality?

There is a sense in which I’ve been chasing the blue dress all my life. The dress that speaks of the out of doors, of sky and sea, an escape from the dark troubled rooms of the house, something that made me feel pretty at time when I felt unattractive and unloved. Looking back across the blue of distance, I see that when worn, my dress temporarily set me dreaming and free, in Solnit’s words, it was …the beauty of that blue that can never be possessed.

There is never a time when I haven’t sought to posses that blue, when I didn’t have at least one blue dress in my wardrobe. Some have been memorable. There was a Biba dress bought in the Abingdon Road store in Kensington, there was a Laura Ashley print, left beneath a bed after a hasty retreat, posted on to me. There was the pale, blue, chambray dress, I wore when the children were small. In a blue dress, I can inhabit the best of myself. As someone who struggles endlessly with liking her appearance, a blue dress is a precious thing.

Growing up by the sea meant that getting lost in the blue was an integral part of life. Fortunately, even the muddy brown, estuary on which I lived and played, that fed into the Bristol Channel and which flooded at high tide, often wore a reflection of azure skies.

When I waited for the bus home from school it was on the seafront in Burnham Bay. Here I watched the sea, and the islands of Flat Holme and Steep Holme rising like blue whales before the horizon and the stretch of the Welsh coast. This landscape appears in my first novel, The Sweet Track. It’s there in my short stories too, as in How the Sea Can Save You, from my collection, this One Wild Place. And I cannot imagine writing memoir without it. The view to the horizon, across water, sometimes marked by a ship, or by distant coastal lights was perhaps the closest I came to the longing of which Solnit writes; to distance as emotion and desire. In that distance stories were told, like my grandmother’s tales of watching for the German invader, who should he come upstream would have found her, and her children, with their heads in the gas oven, so she said.

My dreams of happier times were made there, on that estuary, in that Bay, when I saw beyond what I lived, the possibilities of discovery and of other lives. It was where I lost myself. It was where I made the first small poems in my head. It was where my imagination grew. It was where I became a writer.

Thank you for reading

Avril x

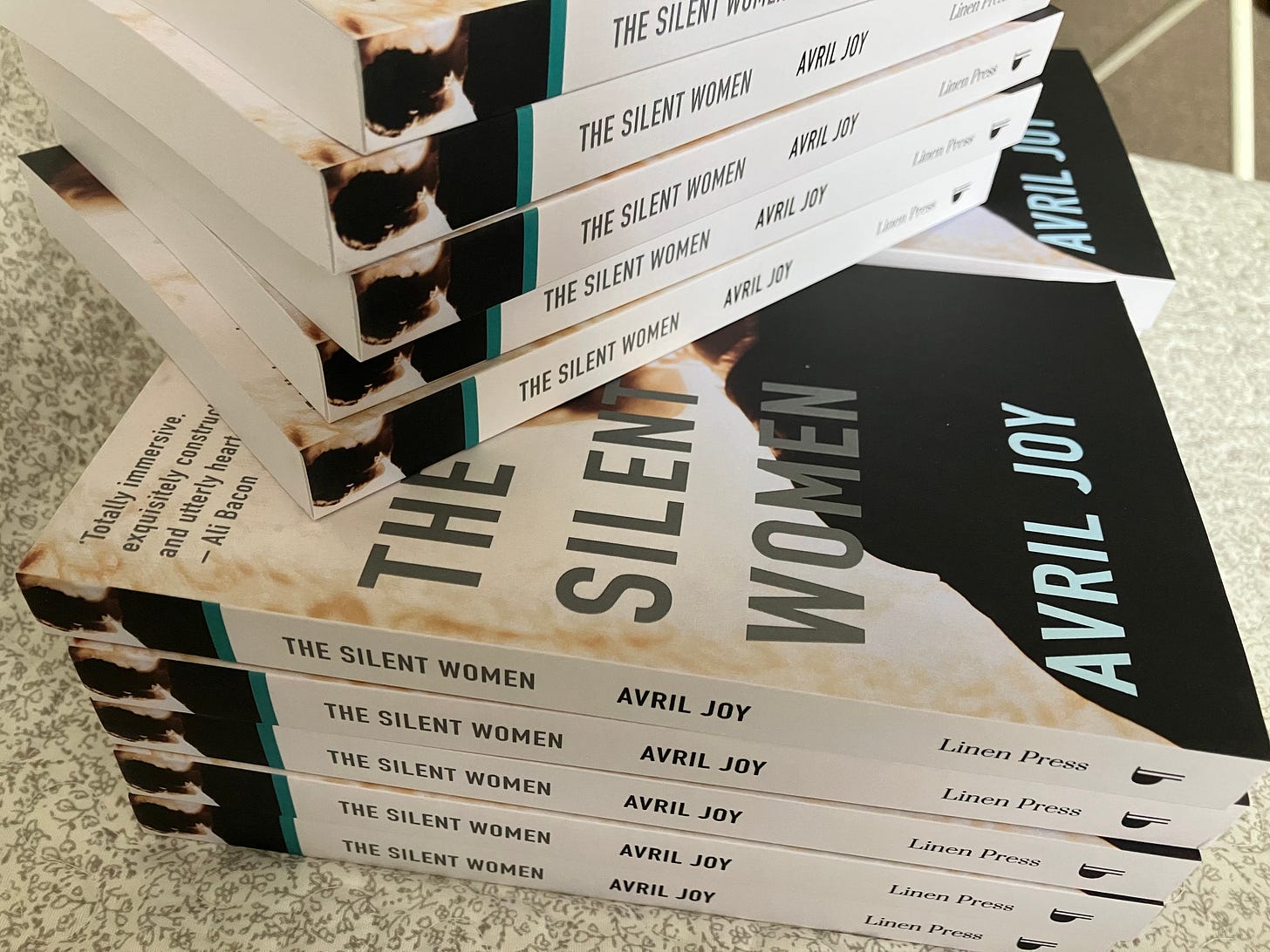

P.S. Coming back from sunshine to rain wasn’t all bad - I returned to these, and a lovely meal cooked by John - a great welcome home!