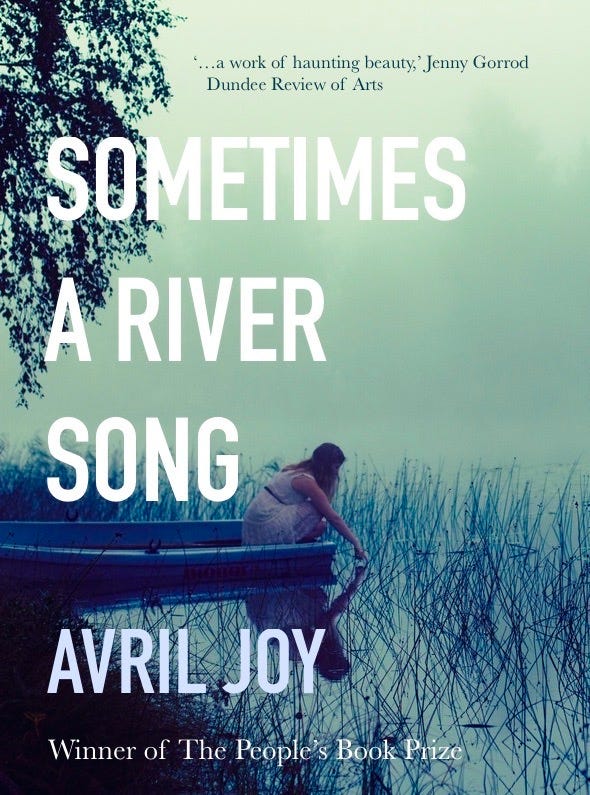

On the advice of my physio, Christine, who is brilliant–and if you’re reading this Christine, I’m keeping up with the exercises–I’m trying to stay away from the computer as much as possible. So, rather than type away at something new, here is a piece I wrote some time ago and which appeared online on The Literary Sofa. It’s about ignoring advice, writing what you don’t know and about my novel, Sometimes a River Song.

As writers we are persuaded that we should, ‘write what we know.’ It’s arguably the most famous piece of writing advice, attributed it seems to both Twain and Hemingway. As new writers unsure of our ground, vulnerable, scared of making mistakes or seeming foolish it makes sense to write what we know. It was advice I took seriously when I began writing. But when Isabel invited me onto The Literary Sofa to talk about writing my novel, Sometimes A River Song, and suggested I might like to do a Writers on Location piece, it was time to confess. I hadn’t been on location. I had never been to Arkansas. Not even close. I hadn’t explored its mountains and forests or sailed its great rivers down to the Mississippi Delta, and yet place, in particular an Arkansas river, was the thread on which the novel hung. It began and ended with the river and the river was constant throughout.

So how did I come to write about something so far from my experience, a place and a people I knew nothing of and all set in the 1930s?

One evening, by chance, I watched a documentary film about a river boat community in Arkansas. I was fascinated by this fast-disappearing world and felt straight away that I’d like to write about it, but it wasn’t long before doubts crept in. Who was I to explore these lives in my fiction? I’d never been there. What did I know? I quickly shelved the idea.

Several years later the inspiration re-surfaced, in the shape of a brilliant short story, The Redemption of Galen Pike, by writer Carys Davies. Her story was set in the Wild West, far from her world, and reading it was a light bulb moment for me. Suddenly I found myself thinking again of the documentary, thinking if Davies can do this why can’t I? And so, my river odyssey began, firstly as a number of short stories but I soon found my protagonist Aiyana’s voice and the novel was born. I began to hear her, and I began to live in her world.

I still worried all the time about what I was doing. I worried most about offending the people of Arkansas, about getting things wrong, but whenever my nerve failed something would come along to steady it. Like this Toni Morrison quote which I discovered, printed out and pinned to my wall.

“People say to write about what you know. I’m here to tell you, no one wants to read that, cos you don’t know anything. So write about something you don’t know. And don’t be scared, ever.”

Writing the novel involved a great deal of research, mostly on the internet. It was important to me to be rigorous and I went back again and again to cross check my facts and ideas. I worked hard on this. There were very few written accounts of these communities or archive material. I dug out what there was. I watched Kenny Salway’s Tales of a River Rat, on YouTube. Poured over Turner Browne and Chris Engholm’s words and photographs. Eventually I summoned up the courage to contact Chris and he was kind enough to read a draft of the novel for me and give it the thumbs up from Arkansas.

There were maps and there was fiction too, especially Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, which for me got to the truth of the Great Depression better than any non-fiction account.

Gradually the light dawned: writing what we don’t know is what writers do all the time, whether it’s fiction, sci-fi, fantasy, history, it’s all about creating worlds, using our imagination.

It wasn’t until I reached the end of my novel and could reflect, that I truly realised the paradox, that in writing what we don’t know, we are also writing everything we do know. Hadn’t I grown up on the Somerset Levels, that watery place close to a tidal creek? I’d lived by the river, played by the river, watched it change with the coming of the seasons just as Aiyana had. Wasn’t that landscape and my connection to it one of the hardest things I’d ever had to leave? Then there was the prison, where I worked for many years. I spent nearly a quarter of a century working with women like Aiyana, some who could not read and many who longed for education. And education had been the thing that had most changed my life, as it does Aiyana’s.

We are always writing what we know but we are all imagineers too. It is the job of the writer to imagine. As Rose Tremain says, ‘the trouble about what you know is that it’s finite. Whereas what you don’t know is infinite. I prefer to keep snatching at the infinite. Invention is really the clue to everything.’

Writing what you don’t know can be daunting, but it can be brave, and for me, taking that creative, imaginative, leap is the exciting thing about writing fiction. The rules are there to be broken…

Here is Isabel’s review of the novel

IN BRIEF: My View of Sometimes a River Song

It was astounding to learn that Avril Joy has no personal history with the distinctive Arkansas landscape of her novel, given the vivid and atmospheric handling of the river setting and life surrounding it. The feminist angle to Sometimes a River Song feels organic and of its time, rather than a superimposed 21st century version, and both the story line and the sensuous, lyrical prose testify to the liberating power of literacy. Readers will be affected by Aiyana’s unique voice and the engaging delineation of character and family bonds. Although there are shocking and brutal events, there is beauty and hope in abundance, not to mention love. An immersive and moving novel from small independent Linen Press.

Hi Avril, I think the plot thickens when it comes to writing what we don't know. When we deal with the particularity of a thing in gleaming detail, most can relate to it, if not that world and its trimmings, the themes, emotions and struggle in one way or another resonate with most human beings. Buffing the particular into such a clear shape that it shines universally, makes it identifiable and universal. Thereafter, I think it's about how much work and research one is prepared to do to move the setting of that world away from the one you have at hand.